The Ojibwe and Wild Rice

Among the Ojibwe (Anishinabe-Chippewa) Indians, the harvesting of wild rice is an economic and cultural tradition that goes deep in their historical experience. Wild rice, zizania aquatica—despite its common name, it is a wild grass—grows in the shallow waters of stream deltas and lakes in Wisconsin, Minnesota and southern Ontario. The plant sprouts in April, flowers in mid-summer, and reaches maturity between mid-August and mid-September. The long heads, or panicles, produce heavy grains, which ripen slowly from the top down.

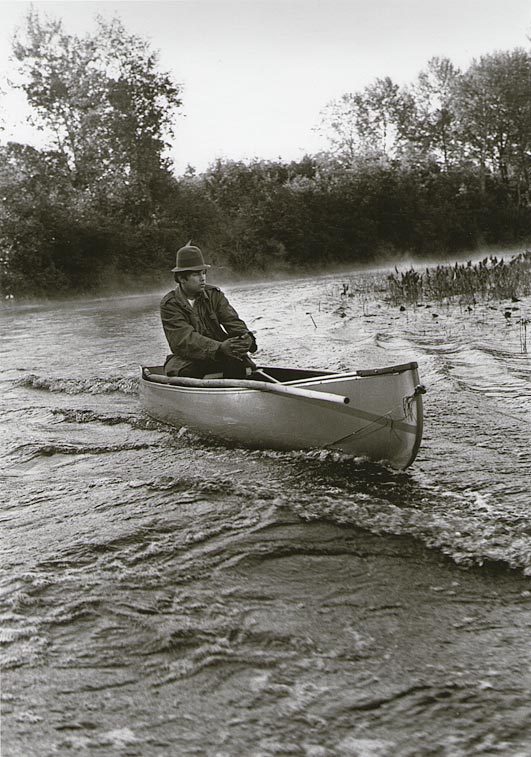

Since the ripening process is slow, Native harvesters must go out and gather the rice daily for two to three weeks. They work in teams of two. One person pushes the canoe through the rice sloughs using a long pole with a forked end—not an easy task. His partner, meanwhile, sits in the bow with a pair of sticks, or “knockers,” and collects the rice. This is done by drawing the heads of the stalks over the edge of the boat with one stick while brushing off the loose ripe grains with the other in a firm gentle motion.

In 1971, my wife, Ruth, and I were privileged to be invited to accompany Anishinabe Indians of the Bad River Reservation in Wisconsin for a day of gathering wild rice. We were issued a flat-bottomed canoe and towed with others down the Bad River to the vast Kakagon Sloughs along the shallow margins of Lake Superior. There, we found that the wild rice fields extended as far as we could see and the canoes dispersed until the harvesters appeared as distant dots across the flat landscape. It was hot and there was no shade and I vividly remember how tiring it was to slowly pole our way through the dense tangle of rice plants in order to arrive within effective photographing proximity of other people.

On another occasion, we visited the Nett Lake community in northern Minnesota during their wild rice harvest. There, thanks to the hospitality of Ira Isham, I was able to photograph members of his family as they dried, parched, threshed, and winnowed their rice using traditional methods.

The photographs shown here are selected from an extensive collection documenting the harvest, the processing, and associated community dances and games. Please contact me for more information about the collection.